Neuromodulation 101: The Science, Treatments, and Benefits for Mental Health

Neuromodulation may sound like science fiction, but in reality, it’s a growing category of evidence-backed treatments that help recalibrate how specific brain circuits work. For people whose depression, anxiety, OCD, or PTSD hasn’t responded to medication or therapy alone, neuromodulation offers another way forward—one that’s precise, carefully studied, and increasingly central to modern psychiatric care.

If you’ve been reading about mental health treatments beyond medication and therapy, you’ve probably run into the word neuromodulation and wondered what it actually means. The word itself can sound technical or even a little intimidating, especially when you’re already navigating symptoms that feel overwhelming.

In simple terms, neuromodulation is a category of medical treatments that interact directly with the brain’s communication systems. Rather than working broadly through the body, these treatments focus on specific brain pathways involved in mood, anxiety, and emotional regulation. For the nearly 3 million Americans with treatment-resistant depression, this more-targeted approach opens up treatment options they didn’t know existed.

Neuromodulation has become increasingly important in psychiatry as our understanding of mental health has shifted from viewing conditions like depression or OCD as purely chemical problems to recognizing the role of disrupted brain circuits. It’s especially relevant for people who feel stuck after trying medications or therapy without enough relief.

In the sections that follow, we’ll break down what neuromodulation is, the main types of treatments available, and what the experience is actually like.

What is neuromodulation?

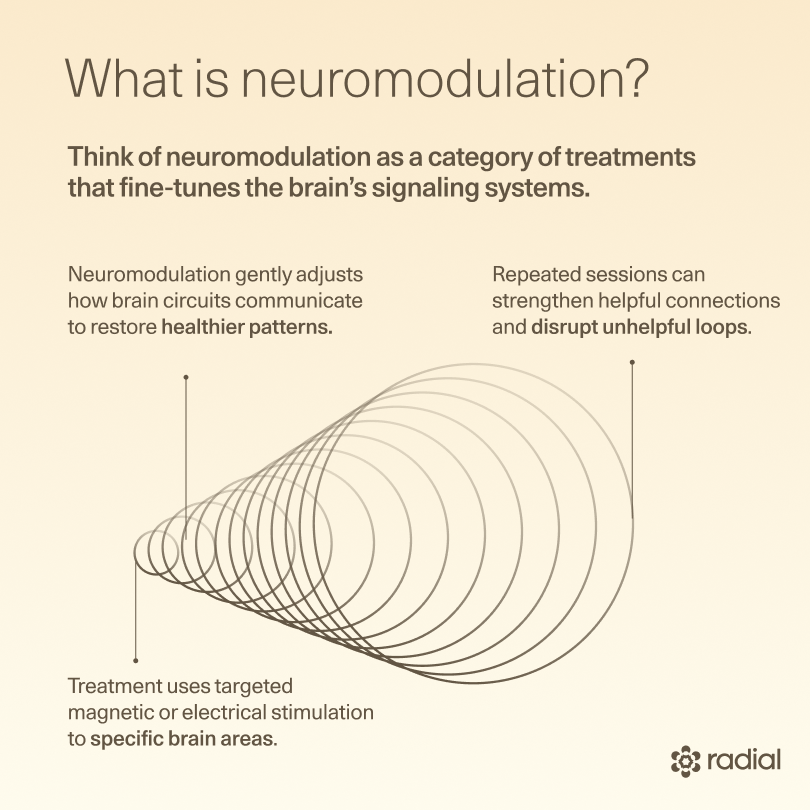

Think of neuromodulation as a category of treatments that fine-tunes the brain’s signaling systems. When certain brain networks are underactive, overactive, or out of sync—as is often the case in depression, OCD, or PTSD—neuromodulation gently nudges those circuits toward healthier patterns. It doesn’t erase memories or change who you are; it just changes how consistently and effectively key pathways fire.

From a science standpoint, neuromodulation works by delivering targeted energy—most often magnetic pulses or electrical stimulation—to precise areas of the brain or nervous system. With repeated sessions, these signals can reshape how neurons communicate, strengthening helpful connections and interrupting unhelpful loops.

Modern neuromodulation works because it’s precise. Clinical studies and tools such as MRI, fMRI, and EEG have helped medical science identify the right areas of the brain to target, so that treatment is both targeted and optimized. That focus is a big reason neuromodulation therapies are generally well-tolerated and don’t come with many of the whole-body side effects associated with medication.

What types of neuromodulation are used in mental health?

Neuromodulation is an umbrella term that covers several different treatments. Some are non-invasive and done in an outpatient clinic. Others are more intensive and reserved for severe, treatment-resistant cases. What they have in common is the goal: helping specific brain circuits communicate more effectively.

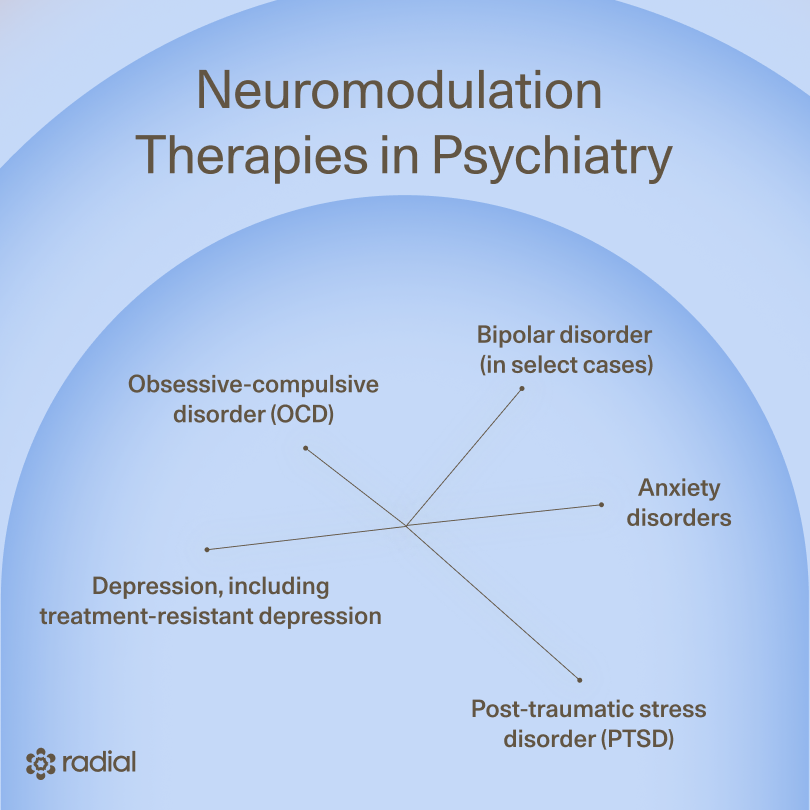

In psychiatry, neuromodulation therapies are most often used to help people whose symptoms haven’t improved enough with medication and psychotherapy alone. Depending on the treatment, they may be used for:

- Depression, including treatment-resistant depression

- Obsessive-compulsive disorder (OCD)

- Anxiety disorders

- Post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD)

- Bipolar disorder (in select cases)

Below, we’ll walk through the main neuromodulation options used in mental health today, starting with the most widely used and moving toward more advanced or emerging treatments.

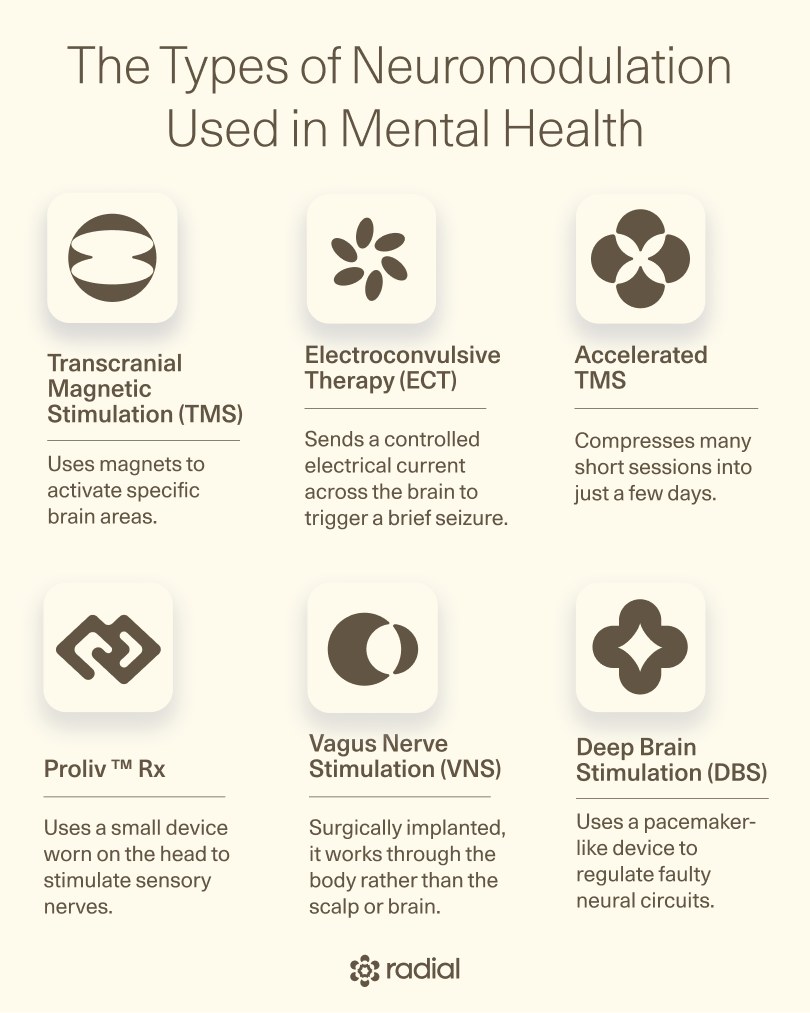

Transcranial magnetic stimulation (TMS)

Transcranial magnetic stimulation (TMS) is the most commonly used non-invasive neuromodulation therapy in psychiatry today.

“Transcranial magnetic stimulation uses magnets to target and activate specific areas of the brain,” says Eugene Grudnikoff, MD, a staff psychiatrist at Radial. “When this type of stimulation is repeated a number of times, the specific circuits learn to fire better. This is not too different from your brain learning a new skill.”

For depression, that typically means targeting areas involved in mood, motivation, and emotional regulation. Here’s the breakdown:

- How it works: A healthcare professional places a cap with a magnetic coil against your scalp, and brief magnetic pulses pass painlessly through the skull to stimulate targeted brain regions. Over time, repeated neurostimulation helps those circuits become more active and coordinated.

- What it’s used for: TMS is FDA-cleared for major depressive disorder, including treatment-resistant depression, OCD, smoking cessation, adolescent depression, and anxious depression. It’s also being studied for conditions like generalized anxiety, PTSD, bipolar disorder, and schizophrenia, adds Grudnikoff.

- Who may be a good candidate: TMS is often considered when someone has tried multiple antidepressants or therapy approaches without enough improvement. It doesn’t require anesthesia, sedation, or recovery time, which makes it accessible for many people.

- Benefits and safety: TMS therapy is considered very safe and well-tolerated. “Depressed patients who have tried multiple medications with no adequate effect will often respond well to TMS,” says Grudnikoff. Serious side effects are rare, and the risk of seizure is extremely low—the risk is in the same ballpark as the risk of seizures from antidepressant medications.

- What it feels like: TMS can be loud and can feel uncomfortable, especially at first, according to Grudnikoff. Some people feel tapping or knocking sensations on the scalp, and sessions typically last just a few minutes. Mild headaches or scalp soreness can happen, but usually fade quickly.

Accelerated TMS

Accelerated TMS is just what it sounds like: TMS, delivered on a faster timeline. Instead of spreading treatments out over several weeks, accelerated TMS compresses many short sessions into just a few days.

One well-known example is SAINT® TMS, a protocol that uses advanced brain mapping and frequent stimulation sessions to speed up symptom relief for some people with severe or treatment-resistant depression. Recently, the SWIFT protocol became the second accelerated TMS protocol to be cleared by the FDA.

According to Grudnikoff, here’s what to know:

- How it works: Accelerated TMS uses the same magnetic stimulation as standard TMS, just on a faster timeline. A healthcare professional places a magnetic coil against your scalp, and brief pulses stimulate specific brain circuits involved in mood and emotional regulation. The difference is scheduling: instead of spreading sessions out over weeks, accelerated TMS delivers many short treatments in a single day, repeated over a few days, so the brain gets more stimulation in a shorter window.

- What it’s used for: Accelerated TMS is used for the same conditions as traditional TMS, including major depressive disorder and treatment-resistant depression. It’s often explored when faster symptom relief is needed or when standard treatment timelines aren’t practical. Research is also ongoing for other conditions, like OCD.

- Who may be a good candidate: This approach may make sense if you’ve tried multiple medications without enough relief, need results sooner, or can’t commit to daily visits for several weeks. Because treatment days are longer and more intensive, clinicians take extra care to make sure it’s a safe and appropriate option for each person.

- Benefits and safety: The biggest advantage of accelerated TMS is speed—some people notice improvement within days instead of weeks. Side effects are similar to those of standard TMS and usually manageable. Serious side effects remain very rare when treatment is delivered under proper medical supervision.

- What it feels like: Accelerated TMS feels much like regular TMS: a loud clicking sound and a tapping sensation on the scalp during each session. Each treatment is brief, with breaks in between, but the day itself can feel long. Most people tolerate it well, and any discomfort typically becomes easier to manage as treatment goes on.

Electroconvulsive therapy (ECT)

Electroconvulsive therapy (ECT) is one of the oldest and most well-known brain-based treatments in psychiatry…and also one of the most misunderstood.

While it can be life-saving in certain situations, it works very differently from newer neuromodulation therapies like TMS. Understanding what ECT is (and isn’t) can help put its benefits and risks into clearer context:

- How it works: Instead of targeting specific brain circuits, ECT sends a controlled electrical current across the brain to trigger a brief, therapeutic seizure. While the exact reason it works isn’t fully understood, this process can quickly change overall brain activity in ways that reduce severe symptoms. Because of this, ECT is not a precise or targeted treatment.

- What it’s used for: ECT therapy is most often used for severe or life-threatening depression, especially when someone is at high risk of harm, experiencing psychosis, or unable to function day to day. It can also be used in certain cases of bipolar disorder, schizophrenia, schizoaffective disorder, and catatonia.

- Who may be a good candidate: ECT is usually considered only after other treatments—such as medication, therapy, or neuromodulation options like TMS—haven’t helped enough, or when symptoms are so severe that waiting isn’t safe. The treatment requires anesthesia and close medical monitoring, so it’s reserved for carefully selected situations.

- Benefits and safety: ECT can be highly effective, particularly for severe depression, and often works faster than other treatments. At the same time, it comes with important risks. Memory problems—especially around the time of treatment—are common, and some people experience longer-lasting memory issues. These risks are carefully weighed before treatment begins.

- What it feels like: ECT is done under general anesthesia, so you’re asleep during the procedure and don’t feel the stimulation itself. Afterward, it’s common to feel groggy, confused, or have a headache for a short time. Memory gaps for recent events can also occur, especially with repeated sessions.

Vagus nerve stimulation (VNS)

Vagus nerve stimulation (VNS) is a form of neuromodulation that works through the body rather than directly through the scalp or brain. It's surgically implanted, so it stays with you wherever you go.

“You can think of VNS as a kind of brain pacemaker,” says MaryEllen Eller, MD, the southeast regional medical director at Radial. “A small device gently stimulates the vagus nerve in your neck, sending signals up to the brain and influencing how different brain circuits function.”

Here’s what to know about VNS, according to Eller:

- How it works: The vagus nerve is one of the body’s main communication highways. It runs from the brainstem through the torso, where it influences heart rate, digestion, breathing, and mood. A VNS system uses a small neuromodulation device placed in the upper chest and a thin wire wrapped around the vagus nerve in the neck to send gentle, timed signals up to the brain. Over time, those signals help calm and rebalance the brain circuits involved in mood.

- What it’s used for: VNS is FDA-approved for epilepsy and treatment-resistant depression, and it’s also used in certain cases of post-stroke rehabilitation. In mental health care, it’s considered when depression has been long-lasting and severe, and when multiple treatments haven’t brought enough relief.

- Who may be a good candidate: VNS isn’t something clinicians jump to early. It’s usually discussed after medications, therapy, TMS, and sometimes ECT haven’t helped enough. Because it involves a surgical implant, careful evaluation is essential to make sure the potential benefits outweigh the risks for each individual.

- Benefits and safety: VNS is not a quick fix. Improvements tend to build slowly over months, which can actually be reassuring for some people—it’s a steady, gradual shift rather than a sudden jolt. Many people tolerate the device well, and side effects are usually related to the stimulation itself rather than whole-body effects.

- What it feels like: The procedure to place a VNS device is generally straightforward and done under anesthesia. It involves two small incisions (one near the collarbone for the device itself and one on the left side of the neck for the wire), and most people go home the same day. Recovery usually takes a week or two. When the device is turned on and slowly adjusted, many people barely notice it. Others feel mild sensations during stimulation, like a tickle in the throat, a brief change in voice, light coughing, or a gentle tugging feeling in the neck. These sensations are usually temporary, tend to fade as the body adjusts, and can often be eased by fine-tuning the settings.

Deep brain stimulation (DBS)

“Deep brain stimulation (DBS) is an advanced neuromodulation treatment that uses a pacemaker-like device to regulate faulty neural circuits,” says Eller. Because it involves surgery, DBS is reserved for the most severe, treatment-resistant cases.

Here’s a closer look at DBS, according to Eller:

- How it works: During DBS, a surgeon places very thin electrodes into specific areas of the brain that are closely linked to your symptoms. These electrodes send steady, low-level electrical pulses that help calm and normalize how those circuits communicate. The electrodes connect to a small device implanted under the skin near the collarbone, which quietly does its job in the background, sending signals that help prevent the brain from getting locked into loops of anxiety, fear, or low mood.

- What it’s used for: DBS is FDA-approved for OCD when symptoms haven’t improved with medications, exposure therapy, TMS, or ECT. It’s also widely used for neurological conditions like Parkinson’s disease and essential tremor. For depression, though, DBS is still considered investigational. While early results are encouraging, it’s currently available only through clinical trials for people with severe, treatment-resistant depression.

- Who may be a good candidate: DBS is never a first step. It’s considered only after many other treatments have failed, often over years. Because the process is complex, anyone being evaluated for DBS undergoes a thorough, thoughtful assessment with both psychiatric and surgical specialists.

- Benefits and safety: For people with severe OCD, DBS can lead to meaningful, lasting improvement. Studies show that many patients experience a significant reduction in symptoms over time, often as the brain gradually adapts to the stimulation. Improvements tend to unfold slowly, over months rather than weeks. Like any brain surgery, DBS carries risks, which is why the decision to move forward is made carefully and collaboratively.

- What it feels like: The surgery itself takes several hours and is guided by detailed brain imaging. You’re sedated for parts of it and awake for others—not because it’s painful, but because your responses help ensure the electrodes are placed exactly where they need to be. After surgery, the device is programmed slowly over a series of visits. Most people don’t feel the stimulation at all; instead, changes show up gradually as symptoms ease and daily life becomes more manageable.

External Combined Occipital and Trigeminal Afferent Nerve Stimulation (eCOT-AS)

eCOT-AS (which goes by the name brand Proliv™ Rx) is a newer, non-invasive form of neuromodulation that’s designed to be used at home or in a clinic. Instead of working through magnets or surgery, it uses a small, battery-powered headset to gently stimulate sensory nerves on the scalp that connect to deeper brain circuits involved in mood.

Here’s what to know:

- How it works: Using Proliv™ Rx is pretty straightforward. You moisten a few small pads, place them in the headset, and wear it for about 40 minutes, twice a day, over the course of eight weeks. The stimulation is mild and often feels like a soft, shifting sensation across the front and back of your head. By stimulating sensory nerves, the device helps influence the brain networks that play a role in depression.

- What it’s used for: eCOT-AS is FDA-approved for major depressive disorder in adults whose symptoms haven’t improved enough with medication (especially those who want something non-invasive and flexible).

- Who may be a good candidate: This approach may be worth exploring if you’ve tried antidepressants without getting the relief you hoped for and are looking for an option that fits more easily into daily life. As with any neuromodulation treatment, a clinician can help determine whether it’s a good match for your situation.

- Benefits and safety: In clinical studies, people using Proliv™ Rx were more likely to reach remission than those using a placebo device, even those with harder-to-treat depression (about 21.3% versus 6%). About 95% of people in the study stuck to the treatment schedule (that’s no small feat in medicine), and side effects were generally mild and limited to the scalp.

- What it feels like: Most people describe the sensation as noticeable but not uncomfortable—more like a gentle tingling or movement across the head. Because the stimulation is low-intensity, you can usually go about your day as usual during or after a session.

Transcranial Direct Current Stimulation (tDCS)

Transcranial direct current stimulation (tDCS) is a gentle, non-invasive form of neuromodulation that uses a very low electrical current to influence brain activity. One of the most well-known examples is Flow™, an at-home tDCS headset designed for people with depression who want a more accessible treatment option.

- How it works: tDCS uses two small electrodes placed on the scalp to deliver a steady, low-level electrical current to targeted brain regions—most often the prefrontal cortex, an area involved in mood regulation. The current is not strong enough to make neurons fire directly. Instead, it slightly shifts how likely those neurons are to activate, helping underactive circuits work more effectively over time. With Flow™, treatment is typically done at home, following a structured schedule set by a clinician.

- What it’s used for: Flow™ tDCS is FDA-cleared for the treatment of major depressive disorder in adults. It’s designed as a non-invasive option that can be used outside of a clinic, often alongside other forms of care such as medication, therapy, or behavioral interventions.

- Who may be a good candidate: Flow tDCS may be a fit for people with depression who haven’t found enough relief from medication alone, prefer an at-home option, or aren’t able to attend frequent in-clinic treatments. As with all neuromodulation therapies, a clinician’s evaluation is important to determine whether it’s appropriate for your symptoms and history.

- Benefits and safety: tDCS is generally well tolerated, with side effects that tend to be mild and localized rather than systemic. In clinical trials of Flow™, participants showed meaningful improvement in depression symptoms, with remission rates higher than placebo. Because the stimulation is low-intensity, tDCS does not carry the same risks as more invasive neuromodulation treatments.

- What it feels like: Most people describe tDCS as a mild tingling, warmth, or itching sensation under the electrodes, especially at the beginning of a session. These sensations usually fade quickly, and many people find the experience easy to tolerate. Because treatment is done at home, sessions can often fit more smoothly into daily routines.

Emerging and adjacent treatments

Alongside established neuromodulation therapies, researchers are actively exploring new ways to influence brain circuits more gently, precisely, or conveniently. Many of these treatments are still in development or early clinical use, but they offer a glimpse into where mental health care is headed:

- Transcranial focused ultrasound neuromodulation (tFUS): tFUS uses sound waves—rather than magnets or electricity—to influence brain activity. These sound waves can be aimed at very specific brain regions without surgery, which is part of what makes the approach so promising. At lower intensities, ultrasound doesn’t damage tissue; instead, it gently alters how neurons fire. tFUS is still being studied for conditions like depression and other psychiatric disorders, and while it’s far from FDA approval, early research has been encouraging.

- Transcranial alternating current stimulation (tACS): tACS is similar to tDCS, but instead of a steady current, it delivers a gentle, rhythmic electrical pattern. The idea is to help synchronize brain waves that may be out of rhythm in certain mental health conditions. Research is ongoing, and while tACS is not yet widely used in clinical psychiatry, it’s being studied for depression, anxiety, and OCD.

- Magnetic seizure therapy (MST): Magnetic seizure therapy aims to combine the effectiveness of ECT with more precise targeting. It uses powerful magnetic pulses to induce a brief, controlled seizure under anesthesia. This is similar to ECT, but with stimulation that’s focused more narrowly on specific brain regions, says Eller. MST is still in clinical trials and not FDA-approved, but early results suggest it may reduce depressive symptoms with fewer cognitive side effects than traditional ECT.

- Wearable and external neuromodulation devices: Wearable devices marketed to “stimulate the nervous system” or “balance mood” are increasingly common, but many deliver low-level stimulation and have limited evidence for mental health use. However, the GammaCore™ nVNS device is FDA-cleared for conditions like migraine and cluster headache. Research into its mental health applications is still evolving, which is why these devices should be seen as condition-specific tools—not general mood treatments—and discussed with a clinician before use, says Eller.

- AI-driven and closed-loop neuromodulation: One of the most exciting areas of research involves systems that can adjust stimulation in real time. These “closed-loop” technologies use data—such as brain signals or symptom patterns—to automatically refine treatment. The goal is to deliver the right amount of stimulation at the right moment, rather than relying on fixed settings. While still largely experimental, this approach could eventually make neuromodulation more personalized and responsive.

What are other types of neuromodulation and what do they treat?

While we’re focusing on neuromodulation in mental health, these same principles are transforming care in other areas of medicine, too. In many cases, the goal is similar: using targeted stimulation to calm overactive signals, restore balance, or improve communication between the brain and the body.

Here are a few other common forms of neuromodulation and what they’re typically used for.

- Spinal cord stimulation: This type of neuromodulation delivers electrical signals to the spinal cord to help block or reduce chronic pain signals before they reach the brain. It’s most often used for long-standing back pain, nerve pain, or pain that hasn’t responded to surgery or medication.

- Peripheral nerve stimulation: Peripheral nerve stimulation targets specific nerves outside the brain and spinal cord. By stimulating a particular nerve (like one involved in migraine or limb pain), this approach can reduce pain or abnormal sensations in a focused, localized way.

- Sacral nerve stimulation: Sacral nerve stimulation works on nerves in the lower back that control bladder, bowel, and pelvic floor function. It’s commonly used to treat conditions like urinary incontinence, bowel control problems, or certain pelvic pain disorders when other treatments haven’t helped.

- Gastric and colonic stimulation: These therapies stimulate nerves that help regulate digestion and gut movement. They’re used in select cases of severe digestive disorders (like gastroparesis or chronic constipation) to improve how the stomach or colon moves food through the body.

- Carotid artery stimulation: Carotid artery stimulation targets sensors in the carotid artery that help regulate blood pressure. By stimulating these receptors, the therapy can help lower blood pressure in people with severe hypertension that hasn’t responded to medication.

The bottom line

Neuromodulation reflects a growing understanding of mental health—one that recognizes how brain circuits shape mood, anxiety, and behavior. These treatments don’t replace medication or therapy; they add another option when common approaches like antidepressants don’t work.

For some people, especially those who’ve been living with symptoms for a long time, neuromodulation can open a new path forward for depression recovery. For others, it becomes one piece of a larger, ongoing care plan. What matters most is that treatment is personalized, thoughtful, and guided by clinicians who take the time to understand your experience, your history, and your goals.

Key takeaways

- Neuromodulation is a category of treatments that gently influence how specific brain circuits communicate.

- These therapies are often considered when medication or therapy alone hasn’t provided enough relief.

- Options range from non-invasive treatments like TMS to more advanced, surgical approaches like VNS and DBS.

- Many neuromodulation treatments are well tolerated and don’t carry the same whole-body side effects as medication.

- Choosing the right treatment is highly individual and works best with guidance from a team experienced in interventional psychiatry.

Frequently asked questions (FAQs)

How does neuromodulation work?

Neuromodulation works by changing how certain brain circuits send signals. Using magnetic, electrical, or implanted stimulation, these treatments help underactive or misfiring networks function more smoothly over time.

What conditions are treated with neuromodulation?

In mental health care, neuromodulation is most commonly used to treat depression (including treatment-resistant depression), OCD, and, in some cases, anxiety disorders, bipolar disorder, schizophrenia, and PTSD. Some treatments are FDA-approved, while others are still being studied or available through clinical trials.

What is an example of a neuromodulation device?

Examples include TMS machines used in outpatient clinics, implanted devices like vagus nerve stimulators, and deep brain stimulation systems. Each device is designed for a specific purpose and level of precision, depending on the condition being treated.

Deep dive recommendations:

- An academic book: A PRACTICAL GUIDE TO TRANSCRANIAL MAGNETIC STIMULATION

- How to Explain TMS on the Carlat Psychiatry Podcast.

- “The Most Impressive Therapy I’ve Ever Tried” — Tim Ferriss On Transcranial Magnetic Stimulation

- Owen and Carlene on Soft White Underbelly part 1

- Owen on Soft White Underbelly part 2

Editorial Standards

At Radial, we believe better health starts with trusted information. Our mission is to empower readers with accurate, accessible, and compassionate content rooted in evidence-based research and reviewed by qualified medical professionals. We’re committed to ensuring the quality and trustworthiness of our content and editorial process–and providing information that is up-to-date, accurate, and relies on evidence-based research and peer-reviewed journals. Learn more about our editorial process.

Let's connect

Get started with finding the right treatment for you or someone you care about

Get started