CPTSD vs PTSD: What’s the Difference?

Feeling stuck in survival mode and wondering if it’s PTSD—or something deeper? Understanding CPTSD vs. PTSD is key to finding the right path forward and finally starting to heal.

If you’ve ever found yourself Googling “CPTSD vs PTSD” at 2 a.m., wondering why your trauma feels so layered, long-lasting, or just different, you’re not alone. Trauma doesn’t always look the same or heal the same way. While post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) often develops after a single life-threatening or deeply distressing event, complex post-traumatic stress disorder (CPTSD) (which is different from chronic PTSD) can stem from ongoing, repeated trauma that chips away at your sense of safety and self over time.

On paper, PTSD and CPTSD live in different rulebooks—the DSM-5-TR (the U.S. diagnostic manual) covers one, the ICD-11 (used internationally), the other. But in real life, the difference between the two can feel blurrier. What matters most isn’t the acronym—it’s that your pain is validated and that healing is possible.

This guide breaks down the key differences between PTSD and CPTSD—how they show up, how they’re treated, and most importantly, how to find hope and healing no matter which diagnosis applies to you (or someone you love).

What is PTSD?

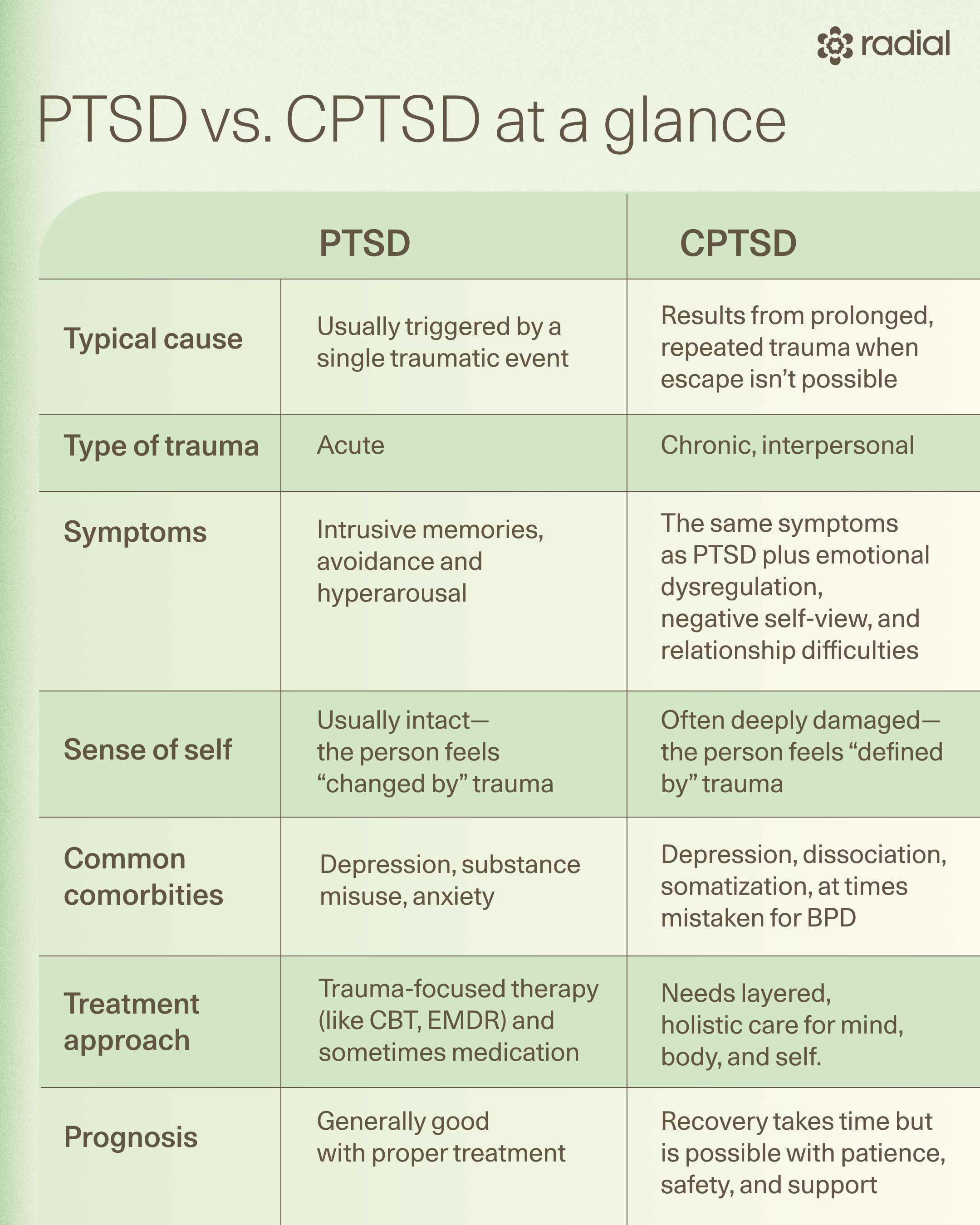

Post-traumatic stress disorder, or PTSD, is a debilitating mental health condition that can develop after experiencing or witnessing a traumatic event. PTSD develops when the brain and body stay stuck in survival mode long after the danger has passed. About 6% of people will experience PTSD in their lifetime, making it far more common than most realize.

The Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM-5-TR)—the go-to guide for diagnosing mental health conditions—defines a PTSD diagnosis through a few key clusters of symptoms that can look different from person to person:

- Intrusive memories or flashbacks that make you feel as if the event is happening all over again

- Avoidance behaviors, like steering clear of people, places, or conversations that remind you of the trauma

- Negative mood or thoughts, including guilt, shame, detachment, or hopelessness

- Heightened arousal, such as irritability, jumpiness, poor sleep, or constant vigilance

To meet the diagnosis, these symptoms must last at least a month and significantly impact daily life, and can’t be explained by substances or another medical condition.

Let’s unpack PTSD in more depth—including how it differs from complex PTSD—and explore both conventional and emerging treatments to help you or someone you love find a path toward recovery.

What is complex PTSD (CPTSD)?

Complex post-traumatic stress disorder (CPTSD) is a relatively new diagnosis officially recognized in the International Classification of Diseases (ICD-11) but not in the DSM-5-TR (the diagnostic manual most often used in the United States). In other words, CPTSD isn't recognized in the classification system that is most used in the USA, but healthcare providers in the United States are perfectly aware that it exists anyway.

So, whether the term exists in a particular manual isn’t the most important point. Many clinicians have long recognized CPTSD as distinct, and its symptoms often show up in other diagnoses, like PTSD with dissociative features or borderline personality disorder.

Even though it’s new to the official books, CPTSD isn’t rare. Research suggests it affects roughly 1%–8% of the general population—and up to half of people receiving care in mental health facilities. What sets CPTSD apart is how the trauma happens. Rather than a single terrifying event, it typically stems from prolonged or repeated trauma, experiences like ongoing childhood abuse, domestic violence, captivity, or chronic neglect, where escape feels impossible.

To qualify for a CPTSD diagnosis, a person must first meet the three core symptom clusters of PTSD, says Aron Tendler, MD, diplomate of the American Board of Psychiatry and Neurology & American Board of Obesity Medicine:

- Recurring intrusive memories or flashbacks

- Avoidance of trauma reminders

- Heightened arousal or reactivity

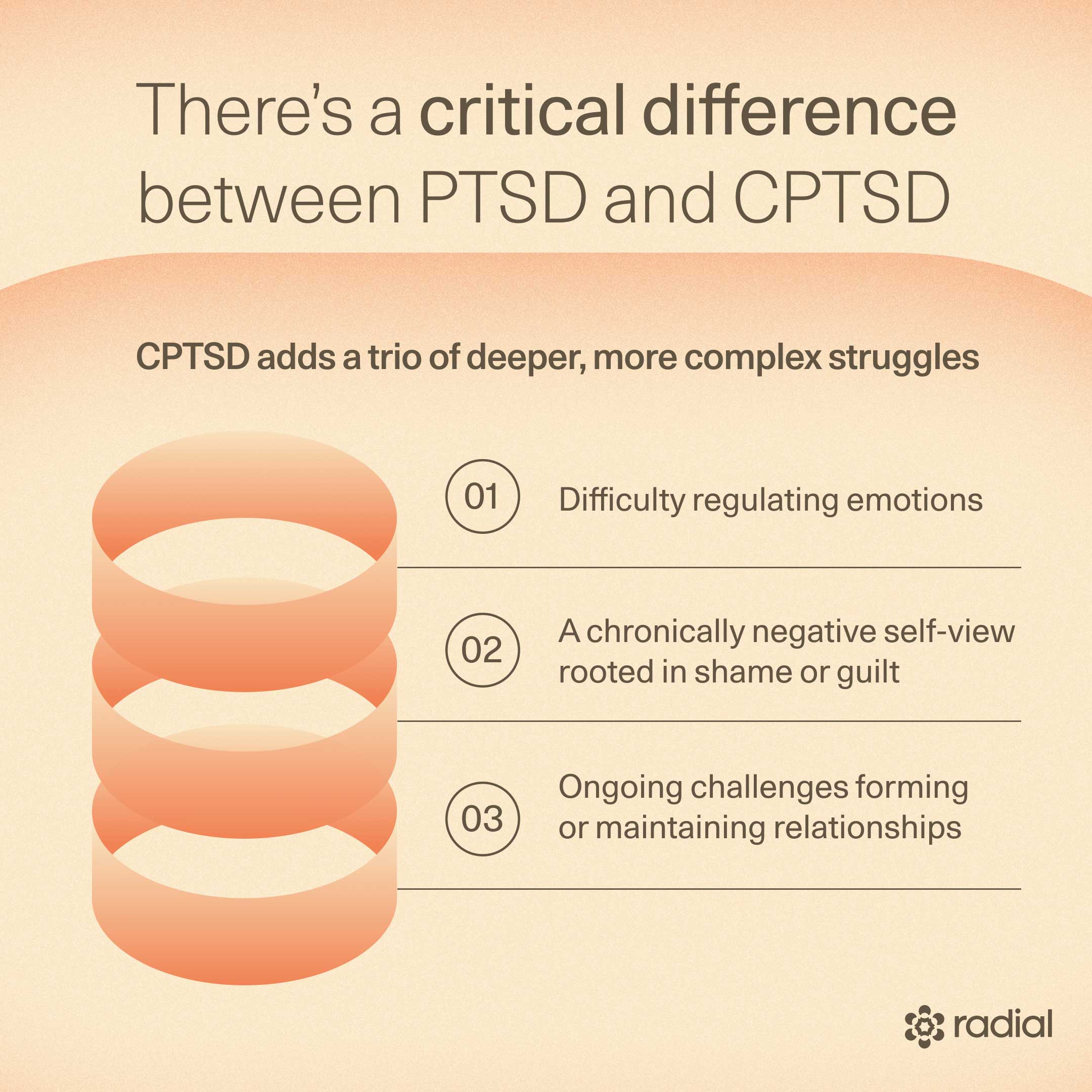

But CPTSD goes further. On top of these, there are three additional clusters of CPTSD symptoms that reflect the deep, long-term impact of repeated trauma (also known as disturbances in self-organization), explains Dr. Tendler:

- Affect dysregulation (trouble managing intense emotions)

- Negative self-concept (feeling worthless, ashamed, or fundamentally “broken”)

- Relationship difficulties (struggling to trust, connect, or feel safe with others)

“Complex PTSD is often harder to treat because it’s seen as an enduring personality change—both by patients and their providers,” explains Dr. Tendler. And since the diagnosis is relatively new, understanding is still evolving. There’s limited data on the most effective treatments, and diagnosis can be tricky, especially when symptoms overlap with other conditions (we’ll dig into that later), he says.

Still, there’s hope. Many of the same therapies that help with PTSD—like CBT and PRISM—appear to also support recovery from CPTSD, though experts often recommend a phased, multi-component approach tailored to each person’s needs.

Later in this article, we’ll break down how CPTSD differs from PTSD and the treatment paths that can help you rebuild a sense of safety, self-worth, and connection if you’re dealing with this condition.

Causes and risk factors: PTSD vs. CPTSD

In both PTSD and CPTSD, certain risk factors can increase vulnerability. For PTSD, triggers might include:

- Previous traumatic experiences (especially in childhood)

- Witnessing or experiencing serious injury or death

- Feeling extreme fear or helplessness

- Lacking social support after the event

- Coping with major life stressors like grief, pain, or job loss

- A personal or family history of mental illness or substance use

Similarly, research shows childhood sexual abuse is one of the strongest CPTSD causes, with those affected nearly three times more likely to develop the condition. Likewise, physical abuse and emotional neglect in childhood also raise the risk of CPTSD. While the data on childhood complex PTSD isn’t up to speed yet, these experiences during development can alter brain pathways that control emotion and threat response, increasing the likelihood of severe emotional dysregulation later in life.

Other factors—like lifelong physical abuse and being a woman—can also increase a person’s odds for CPTSD.

Though PTSD and complex PTSD share some overlapping risk factors, what separates them is how the trauma happens. PTSD often stems from a single, overwhelming event—a car crash, a natural disaster, a physical or sexual assault—and can even develop indirectly (for example, from learning about a loved one’s trauma).

On the other hand, CPTSD almost always involves the direct experience of trauma that is prolonged, repetitive, and inescapable—think torture, captivity, domestic violence, or chronic childhood abuse—the kind that erodes a person’s sense of safety and self over time.

Symptoms: Where PTSD and CPTSD overlap and differ

As mentioned earlier, the core symptoms of PTSD are:

- Intrusive memories or flashbacks

- Avoidance of trauma reminders

- Hyperarousal (think jumpiness, irritability, or trouble sleeping)

In addition to these core symptoms, CPTSD also involves:

- Difficulty regulating emotions (affect dysregulation)

- A chronically negative self-view rooted in shame or guilt

- Ongoing challenges forming or maintaining relationships

While the DSM-5 hasn’t recognized CPTSD as its own diagnosis, it does acknowledge some of the same complex symptoms under the dissociative subtype of PTSD. It also lists depersonalization (feeling detached from yourself) and derealization (feeling like the world isn’t real) as additional symptoms of the dissociative subtype.

Still, other research suggests CPTSD stands apart as a distinct diagnosis. That’s because people who would meet the criteria often show greater emotional dysregulation, deeper attachment wounds, and more pronounced changes in brain regions tied to emotion and cognition, like the hippocampus and prefrontal cortex.

A note on gender

While trauma doesn’t discriminate, symptoms can differ by gender. Women with PTSD, for instance, are more likely to feel easily startled, emotionally numb, or avoidant, and often struggle with depression or anxiety more than men. They also tend to experience symptoms for longer—about four years on average versus one. Interestingly, women are less likely than men to develop substance use issues after trauma.

Data on gender differences in CPTSD is still scarce, but we do know that being female increases the risk of developing the symptoms associated with the condition—yet another reminder that trauma, biology, and social context all intertwine in complex ways.

Diagnosis and misdiagnosis

Accurate diagnosis is key to effective treatment for both PTSD and complex PTSD. But as the name suggests, CPTSD can be, well, complex, and that makes it trickier to identify and treat.

One big challenge? Overlap with other conditions. “There is an overlap and occasional difficulty distinguishing between individuals with CPTSD and borderline personality disorder,” explains Dr. Tendler. Both can present with traits like unstable relationships, intense emotions, dissociation, impulsivity, irritability, and self-destructive behaviors. CPTSD also frequently coexists with depression, dissociative disorders, somatization (psychological stress showing up as physical symptoms), suicide, and—less commonly—generalized anxiety disorder, which can further muddy the diagnostic waters.

That said, an experienced, trauma-informed clinician should be able to tease apart the differences, says Dr. Tendler. Many use screening tools as a first step, such as questionnaires about lifetime trauma exposure (like the Life Events Checklist or Childhood Trauma Questionnaire) and CPTSD symptom checklists (like the International Trauma Interview or International Trauma Questionnaire), he says. These, paired with in-depth clinical interviews that explore context and lived experience, help form a clearer diagnostic picture.

In short: getting the right diagnosis isn’t just semantics—it’s the foundation for finding the right treatment to begin real healing.

Treatment options

Feeling stuck or hopeless? You’re not alone, and the good news is, both PTSD and complex PTSD (CPTSD) are treatable. There’s a growing toolbox of evidence-based therapies that can help you heal and feel like yourself again.

CPTSD, though, can be a tougher nut to crack. It’s often seen as a more deep-rooted, enduring shift in personality—involving more dissociation (that detached, spaced-out feeling) and overlapping with borderline personality disorder—something that can make recovery feel slower or more complicated for both patients and providers, says Dr. Tendler.

Because CPTSD is still a relatively new diagnosis, the research is in the early stages. “It’s still unclear whether CPTSD requires a different treatment than PTSD,” says Dr. Tendler. But early evidence suggests it might. While PTSD often responds to targeted therapy alone, CPTSD usually calls for a broader approach—one that supports not just the mind, but also the body, the nervous system, relationships, and identity.

The silver lining? Recovery is absolutely possible. If a person didn’t have this personality before the trauma, no matter how long or how many traumas occurred, they can change back to who they were before, Dr. Tendler explains. “The core belief of all psychiatrists is that people can change—at any age—under the right circumstances and motivation,” he adds.

From tried-and-true talk therapies to medications, cutting-edge brain tech, and even lifestyle tools, here’s what the science says about the most effective treatments for PTSD and CPTSD.

Psychotherapy

When it comes to treating PTSD, talk therapy—aka psychotherapy—is the mainstay of care. Decades of research show that trauma-focused psychotherapies like cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT) and eye movement desensitization and reprocessing (EMDR) tend to deliver stronger, longer-lasting results than medication alone.

For complex PTSD (CPTSD), things get trickier. These same therapies can help, but research is still catching up. Early evidence suggests people with CPTSD may also benefit from intensive trauma-focused treatment, just with a few extra considerations and a slower, more gradual approach (more on this later).

Let’s take a look at some evidence-based therapies.

Cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT)

Cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT) is a collection of techniques that help you spot unhelpful thoughts and behavior patterns and replace them with more balanced ones.

Two of the most effective CBT approaches for PTSD are:

- Cognitive processing therapy (CPT): You and your therapist unpack the beliefs you’ve built around your trauma—especially the ones that aren’t serving you—and work to reframe them.

- Prolonged exposure therapy: You slowly and safely confront memories or situations you’ve been avoiding, retraining your brain to see that the danger has passed.

Strong evidence supports CBT for PTSD, and emerging studies show trauma-focused CBT (TF-CBT)—which involves reliving and restructuring traumatic memories—can also help people with CPTSD. That said, diving too fast into exposure work can backfire for folks with deep, complex trauma or dissociation. Many people with CPTSD need time to stabilize before facing traumatic material head-on.

EMDR

EMDR (eye movement desensitization and reprocessing), developed in the late ’80s, takes a different approach. While recalling distressing events, you follow a rhythmic back-and-forth motion—like flashing lights or gentle sounds—which seems to help the brain “re-file” painful memories so they’re less emotionally charged.

Researchers still debate how EMDR works, but plenty of studies show it can reduce PTSD symptoms. The American Psychological Association even recommends it as a second-line treatment. Early evidence also supports EMDR’s potential for CPTSD—and bonus, it’s easy to adapt for telehealth.

Narrative exposure therapy

Narrative exposure therapy (NET) was designed for people who’ve lived through multiple traumas (think refugees or those with long-term abuse histories). In NET, you build a chronological “life story,” integrating traumatic memories into a larger, more coherent narrative. This helps restore identity, dignity, and control—three things trauma tends to steal.

Usually completed in 4–10 sessions, NET has shown promise for reducing PTSD symptoms and may be especially helpful for people with CPTSD who have chronic or repeated trauma.

Phase-based therapy

Because complex PTSD lives up to its name, one-size-fits-all treatment doesn’t always cut it. A phased approach—recommended by international CPTSD guidelines—breaks therapy into three stages:

- Stabilization: Establish safety, manage daily stressors, learn emotion regulation skills, and understand how trauma affects the mind and body.

- Trauma processing: Dive into targeted therapies like CBT or EMDR to work through traumatic memories.

- Reintegration: Rebuild a sense of self, strengthen relationships, and reconnect with work, community, and purpose.

A standout phase-based model is STAIR (Skills Training in Affective and Interpersonal Regulation). It helps rebuild emotional and social skills that early trauma can derail and has shown solid results for CPTSD.

Because CPTSD often involves deep shame, mistrust, and long-term relational wounds, healing takes time. One study found that even after 28 sessions, over half of CPTSD patients still met clinical criteria. All this to say, longer, more flexible treatment may have advantages over other treatment approaches, but additional studies are still needed to confirm what works best for people with CPTSD.

Medication

While talk therapy is usually the first recommendation for PTSD treatment, medication can still play a helpful supporting role. Certain drugs can take the edge off symptoms like anxiety, hyperarousal, and sleep issues—especially when combined with therapy.

That said, meds aren’t a magic fix, and their effectiveness for CPTSD is still unclear. They may ease some symptoms, but they’re less likely to improve the deeper stuff like chronic shame, guilt, or disconnection from others.

Here’s what we know about the most commonly used medications for PTSD:

SSRIs

Selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs) are often prescribed as PTSD medication. Two—sertraline (Zoloft) and paroxetine (Paxil)—are FDA-approved specifically for PTSD.

They work by increasing serotonin, a brain chemical that helps regulate mood, sleep, and stress, and appear to reduce symptoms of PTSD in some people.

That said, SSRIs can come with side effects including nausea, dizziness, sweating, headaches, or sexual changes like low libido or difficulty orgasming. Some people also experience weight gain or increased cholesterol.

SNRIs

Serotonin-norepinephrine reuptake inhibitors (SNRIs)—like venlafaxine (Effexor) and duloxetine (Cymbalta)—target not one, but two neurotransmitters: serotonin and norepinephrine.

That double action can help lift mood and calm anxiety in people with PTSD. The trade-off? They can cause tougher side effects than SSRIs, including higher blood pressure and more challenging withdrawal if stopped abruptly.

Prazosin

Prazosin, originally a blood pressure medication, has become an option for PTSD-related nightmares and poor sleep—a symptom that affects up to 70% of people with PTSD (and is even linked to a greater risk of suicide)

PTSD can trigger surges of norepinephrine, a stress hormone that fuels restless nights and vivid nightmares. Prazosin works by blocking norepinephrine’s effects on the brain’s alpha-1 receptors, quieting that stress response so you can finally catch some zzzs.

Several studies show it can help treat sleep-related problems tied to PTSD.

Neuromodulation therapies

Sometimes, talk therapy and meds don’t fully move the needle for PTSD and CPTSD. That’s where neuromodulation—treatments that use gentle electrical or chemical signals to tweak how your nervous system works to reset or rebalance brain and nerve activity—comes in.

Researchers are exploring a wave of new, science-backed tools that go beyond traditional approaches. While data on CPTSD is still limited, these emerging therapies are showing real promise.

TMS

Transcranial magnetic stimulation (TMS) uses gentle magnetic pulses to stimulate specific brain areas, and it’s already FDA-cleared for depression. With PTSD, the brain’s fear and stress circuits fall out of sync, especially in the prefrontal cortex. TMS helps “reset” those connections.

Early research shows that both high- and low-frequency TMS can ease PTSD symptoms. Side effects are generally mild (think: headaches or scalp tingling). That said, some people may need to avoid it—those with metal implants near the head or a history of seizures should consult their doctor before trying it.

The best part? Unlike exposure therapy, you don’t have to relive traumatic memories to see results.

Neurofeedback

In neurofeedback, you wear a cap that reads brainwave activity and translates it into real-time visual or audio feedback on a computer screen, helping you learn to regulate your own neural responses over time.

One FDA-cleared device, Prism for PTSD, specifically targets the amygdala–prefrontal cortex circuit, which is a hub of the brain’s regulatory system for fear and emotion. There’s even some evidence that it can be “an effective treatment for complex PTSD,” says Dr. Tendler. In one study of women with complex PTSD from childhood sexual abuse, those who added Prism to therapy improved almost three times more than those in therapy alone, with continued progress six months later, he says.

Like with TMS, neurofeedback allows for healing of trauma without reliving the experience of that trauma.

Stellate ganglion block

When you live in constant hyperarousal, your body’s “fight-or-flight” system is stuck in overdrive. Stellate ganglion block (SGB) helps hit pause. The procedure involves a quick injection of anesthetic into a bundle of neck nerves near the voice box.

In one study, over 70% of military members with PTSD saw meaningful improvement lasting up to six months after a single injection. In another study, even non-military patients who didn’t respond to one side improved with treatment on the other, suggesting flexibility in how it can be delivered.

Plus, the procedure is minimally invasive, takes under 30 minutes, and the relief is almost instant for some.

Vagus nerve stimulation

The vagus nerve is your body’s ultimate chill button, regulating heart rate, breathing, and digestion. Vagus nerve stimulation (VNS) sends mild electrical impulses through this nerve to help restore balance to the nervous system. Already FDA-approved for depression (and epilepsy), VNS may also boost the effects of trauma therapy, helping to enhance plasticity in neural networks linked to fear learning.

In a small pilot study, pairing VNS with prolonged exposure therapy led to major improvements in symptoms related to treatment-resistant PTSD that lasted six months beyond treatment. No serious side effects were reported, making it a promising (and surprisingly gentle) option for future research.

Cranial electrical stimulation

Cranial electrical stimulation (CES) delivers a tiny electrical current to the head using electrodes—either clipped to the ears or placed at the temples—to modulate brain and nervous system activity. Devices like Alpha-Stim and Fisher-Wallace Stimulator are already FDA-cleared for anxiety, depression, and insomnia.

While research on PTSD and CPTSD is still early, results are intriguing: in one survey of active-duty service members and veterans, half reported at least 50% improvement in symptoms like anxiety, insomnia, depression, and PTSD. Nearly all participants found CES safe and well-tolerated.

Scientists think CES may nudge the brain toward a calmer “rest and digest” mode by stimulating vagus nerve pathways, but more evidence is needed to confirm exactly how it works and whether it can be an effective treatment for PTSD and/or CPTSD.

Trauma-informed lifestyle and self-care

When you’re healing from PTSD or CPTSD, therapy and medication aren’t the only tools in the box. Sometimes the most powerful medicine is learning how to calm your nervous system and reconnect with your body on your own terms.

Trauma-sensitive yoga

Trauma-sensitive yoga isn’t your average vinyasa class. It’s designed with emotional safety in mind—no forced poses, no unexpected touch, and no pressure to “go deeper.” Instead, teachers offer choices and modifications that help participants feel grounded and in control.

This mindful, body-based approach helps survivors rebuild trust with their bodies and regulate overwhelming emotions.

Research backs it up: a 2023 meta-analysis found trauma-informed yoga to be safe and effective for women with PTSD. Some studies also show that yoga as part of the “reintegration” stage of CPTSD treatment helps people regain a sense of control and connection with their bodies, thoughts, emotions, and relationships.

Other movement-based approaches

For some, healing happens through motion. Movement-based therapies can help bridge the gap between body and mind, especially during CPTSD’s reintegration phase.

- Dance and Movement Therapy (DMT) turns emotional exploration into embodied expression. Through guided movement around themes like trust or empowerment, journaling, and group sharing, participants learn to process emotions safely, and some data shows it can ease difficulties with emotional regulation.

- Basic Body Awareness Therapy (BBAT), led by physiotherapists, uses slow, guided exercises to improve posture, balance, and muscle tension. In one study, adding BBAT to existing treatments helped participants sleep better, manage pain, stay present, and strengthen relationships, all while boosting self-care.

Service dog programs

For veterans and others with CPTSD, service dogs can be more than companions—they’re catalysts for connection. Programs often include training alongside the dog before adoption, helping participants build trust, routine, and responsibility.

Emerging research on veteran service dog programs during phase-based treatments for PTSD shows that training a service dog can increase social connectedness, community participation, self-compassion, and overall quality of life while easing isolation and self-judgment. Who knew tail wags could be so therapeutic?

Acupuncture

Don’t dismiss acupuncture as “new age-y”—it’s got serious science behind it. Early research shows it can help regulate stress hormones, calm the nervous system, and even promote healthy changes in brain structure. For some, it’s a surprisingly powerful way to reset both body and mind.

When and how to get help

Healing from trauma is hard work, but you don’t have to do it solo. If your symptoms are disrupting your relationships, work, or day-to-day life, that’s your cue: it’s time to reach out for help.

But here’s the thing—not all therapists are trained to handle trauma, and finding the right one can make all the difference. When you’re searching, get specific. Using keywords like “Trauma-informed,” “Trauma counseling,” “CPTSD,” “Complex trauma,” or “Trauma recovery” can help you zero in on professionals who actually specialize in this kind of work. Many PTSD specialists also treat CPTSD, but it’s worth confirming.

Once you’ve found someone, ask directly:

- Do you have training or experience working with trauma survivors?

- Have you treated clients with CPTSD before?

Don’t get discouraged if the first therapist isn’t a perfect match—it’s totally normal to try a few before finding your fit. That doesn’t mean you’re too “damaged” to help; it just means healing takes time and the right connection.

And remember: you’re not broken. As Dr. Tendler reminds us, “people can change—at any age—under the right circumstances and motivation.”

If you’re in crisis, please don’t wait to get support. Help is just a call, text, or click away:

Call or text 988 (or chat online) to connect with a trained mental health crisis counselor at the Suicide and Crisis Lifeline.

Veterans: Call 988 and press “1,” text 838255, or chat online with the Veterans Crisis Line.

The bottom line

PTSD and CPTSD can both leave deep marks, but they don’t have to define your future. Understanding the nuances between the two helps you find care that actually fits your needs. Whether that means trauma-focused therapy, neuromodulation treatments, or rebuilding safety through movement and self-compassion, healing happens step by step, and you don’t have to do it alone.

Ready to take that step? Radial can help you access fast-acting, evidence-based treatments that go beyond talk therapy. Connect with a licensed clinician—virtually or in-person—who’ll listen, understand your story, and craft a treatment plan tailored just for you.

Key takeaways

- PTSD and CPTSD overlap and share some core symptoms, but they’re not the same. Both stem from trauma, but CPTSD develops from prolonged, repeated harm that reshapes your sense of self, relationships, and emotional regulation.

- CPTSD treatment needs a bigger toolkit. Traditional trauma therapies can help, but CPTSD may require a phased, integrative approach that heals the body, mind, and nervous system.

- Medication and neuromodulation therapies can make all the difference. Tools like SSRIs, TMS, and neurofeedback can support recovery when talk therapy alone isn’t enough.

- Self-care isn’t fluff—it’s foundational. Trauma-informed yoga, movement therapies, and acupuncture can rebuild connection, trust, and safety from the inside out.

- Healing is absolutely possible. With the right treatment and support, people with PTSD and CPTSD can reclaim who they were before trauma.

Frequently asked questions (FAQs)

How is CPTSD different from PTSD?

PTSD often comes from a single, shattering event while CPTSD usually grows out of repeated trauma, especially in situations where escape wasn’t possible. Both involve three main symptom clusters:

- Intrusive memories or flashbacks

- Avoidance of trauma reminders

- Hyperarousal, like being constantly on edge or jumpy

But CPTSD adds another layer of symptoms. These include:

- Emotional dysregulation (struggling to manage big feelings)

- Negative self-concept (feeling worthless, guilty, or broken)

- Relationship challenges (trouble trusting, connecting, or feeling safe with others)

What is CPTSD often misdiagnosed as?

CPTSD can be slippery to diagnose. It shares a lot of traits—unstable relationships, mood swings, dissociation, irritability—with borderline personality disorder, says Dr. Tendler. It can also show up alongside depression, dissociative disorders, somatization, suicidal thoughts, and sometimes generalized anxiety.

That combo can make things murky, but a skilled, trauma-informed clinician should be able to spot the differences and make the right call.

Is CPTSD worse than PTSD?

“Worse” isn’t quite the right word—both can be profoundly painful—but CPTSD often packs an extra punch. On top of classic PTSD symptoms, people with CPTSD may struggle more with emotional regulation, self-worth, and relationships.

Because it overlaps with other conditions (like borderline personality disorder), it can also be harder to diagnose and treat, which can potentially delay recovery. But with the right support and approach, healing is absolutely possible.

Editorial Standards

At Radial, we believe better health starts with trusted information. Our mission is to empower readers with accurate, accessible, and compassionate content rooted in evidence-based research and reviewed by qualified medical professionals. We’re committed to ensuring the quality and trustworthiness of our content and editorial process–and providing information that is up-to-date, accurate, and relies on evidence-based research and peer-reviewed journals. Learn more about our editorial process.

Let's connect

Get started with finding the right treatment for you or someone you care about

Get started