BPD vs. Bipolar Disorder: What’s the Difference?

Bipolar disorder and borderline personality disorder (BPD) share some similarities, which can make them difficult to distinguish. That said, they are distinct disorders with different causes, symptoms, and treatment approaches. Here’s everything you need to know about BPD vs bipolar disorder, including what these conditions actually are, their differences, and effective treatment options.

Bipolar disorder and borderline personality disorder (BPD) are often confused for one another. Both are mental health conditions that lead to behaviors that aren't healthy for the individual or those around them, and there is some overlap between BPD vs bipolar disorder.

“Clinically, the primary feature they share is mood swings, though both can also involve irritability or impulsiveness,” explains Joshua Bess, MD, the medical director at Seattle Neuropsychiatric Treatment Center.

Despite their similarities, these are two distinct conditions, and any confusion about these disorders ends here. Borderline personality disorder is not the same as bipolar disorder, and we’re about to dive into each condition individually before mapping out the key differences between borderline personality disorder vs bipolar disorder.

What is borderline personality disorder (BPD)?

To understand BPD, we first have to understand what a personality disorder is (and it has nothing to do with personality tests or enneagram types).

A personality disorder is when someone has a long-standing pattern of behaviors and thoughts that are different than what is expected and harm their ability to function in a healthy way. The last part is key, since many of us have a few things that are different about our personalities, but they don’t interfere with our ability to complete everyday tasks, maintain relationships, and achieve our goals.

BPD is one of the most common types of personality disorders, but is still relatively rare, affecting 0.7 to 2.7% of people. “Borderline personality disorder manifests in many different extreme ways of relating to people and the world,” says Ahmed Tahseen, MD, a clinical instructor of psychiatry at Yale University.

These “extreme ways” include acting with anger or impulsiveness, intending harm to oneself or others, and other behaviors often stemming from a fear of abandonment. Dr. Tahseen adds, “These ways usually leave people guarded, leave them sensitive to interactions, and make a lot of things difficult in terms of how they interact with life.”

Causes of BPD

No one knows the exact cause of BPD, though genetic, family, and social factors play a role. It’s among the most "genetic" of psychiatric disorders, with hereditary factors accounting for the majority (55%) of the factors leading up to BPD.

BPD can be exacerbated by a traumatic experience, such as a fear of abandonment or actual abandonment as a child or teen. It can also be triggered by emotional, physical, or sexual abuse, a disrupted family life, or communication issues in the family. Ongoing invalidation from parental figures may also contribute to BPD.

No matter the exact cause or mix of causes, BPD leads to problems in identity (“who am I,”) self-direction (“what am I doing with my life?”), empathy (“why should I care about you?”) and intimacy (“why would anyone love me?”).

.png)

Symptoms of BPD

BPD causes a lack of confidence in yourself and a fear of how others may judge you. This causes distortions, both in terms of interests and how a person with BPD views others around them.

Specific symptoms or borderline personality disorder include:

- Viewing people and things through an extreme perspective (i.e. someone is either all good or all bad)

- Intense feelings that can change quickly and unpredictably

- Unstable, intense relationships

- Extreme fear of abandonment

- Feeling chronically empty or bored

- Intense displays of anger

- Self-injury, usually non-lethal, and/or repeated suicide attempts

- Acting impulsively

- Engaging in risky behaviors, like drug use or unprotected sex

Together, these symptoms make it harder for those with BPD to interact with others in a meaningful way. “It usually leaves people feeling pretty empty and chronically pretty isolated,” says Dr. Tahseen.

BPD can also cause intense emotional swings, aka “BPD episodes.” These tend to be triggered by real or imagined rejection or abandonment as well as interpersonal stressors. These episodes can be as short as a few hours or as long as a couple days.

One hallmark characteristic of a BPD episode is called “splitting.” BPD splitting is a cognitive distortion where circumstances—and often people—are viewed as either all good or all bad.

This black-and-white thinking often leads to a cycle of idealization and devaluation in relationships. One moment, for example, someone with BPD may adore a romantic partner and think they can do no wrong, while the next day they may break-up after a disagreement–even if understood as “small” to their partner.

Diagnosing BPD

Mental health conditions can be misdiagnosed, and BPD is no exception. In fact, the condition has an average “diagnosis gap” of about 18.1 years. That means for many with this condition, symptoms of BPD start in adolescence but are not diagnosed for nearly two decades..

Diagnosis is based on observing the patient over time and looking into their medical and social history. Clinicians often use screening tools to flag potential BPD cases, such as the 10-item McLean Screening Instrument and the Zanarini rating scale, though the screening tools alone are not enough to diagnose someone.

Treatments for BPD

“The foundational treatment for BPD is psychotherapy,” says Dr. Bess. That’s because psychotherapy, a type of talk therapy that explores someone’s past and why they act and think the way they do, helps unravel the traumatic circumstances that motivated someone to develop BPD in the first place.

A potential treatment for BPD is dialectical behavioral therapy (DBT), which combines traditional talk therapy with skill-building sessions in a group. The aim is to develop skills and habits that can help someone better regulate their emotional landscape and more successfully interact with those around them. DBT is especially useful at reducing self-harm and improving how an individual manages their mental well-being and relationships with others.

Other effective treatments exist, including mentalization-based treatment (MBT), transference-focused psychotherapy (TFP), and good psychiatric management (GPM).

MBT is a type of psychotherapy that helps people better understand their own thoughts and emotions, as well as others. Fewer providers specialize in MBT, though it is available at Radial.

GPM combines talk therapy focused on emotional regulation, self-indentity, and interpersonal relationships with practical strategies to help those with BPD overcome challenges and build better relationships.

On the medication front, drugs are sometimes prescribed for BPD mood swings and other specific symptoms, though none have evidence for their effectiveness. ”They don’t get to the root causes of BPD,” says Dr. Bess.

There’s emerging evidence to suggest transcranial magnetic stimulation (TMS), a treatment where magnetic pulses rewire and regulate brain activity in a safe, noninvasive way, helps with depression-related symptoms of BPD. These aren’t the only symptoms TMS may reduce, however. It also helps with mood regulation, impulsivity, cognition, which may help reduce the frequency and severity of BPD episodes.

What is bipolar disorder?

Now let’s switch gears and discuss bipolar disorder, which is a mood disorder, not a personality disorder like BPD.

To understand a mood disorder, let’s first differentiate between moods and the emotions that drive them. As Dr. Bess explains, “Unlike brief ‘emotions,’ moods persist over time, influencing perception, cognition, and behaviors.” He notes that our moods are shaped by both internal and external stimuli.

We all experience different moods. Perhaps one week you feel a bit more bored or stressed while the next you’re energized thanks to exciting weekend plans. Those with bipolar disorder have more variance in moods, meaning they have higher highs and lower lows. Those highs can take the form of mania, which is a state where someone has increased energy, and sometimes also restlessness, irritability, or bipolar rage. The lows are referred to as bipolar depression. Some patients even have “mixed episodes,” which involve having depressive and manic symptoms at the same time.

Compared to BPD, “mood swings in bipolar disorder tend to last longer—several days or a few weeks for manic or mixed states, and weeks-to-months-to-years for depressed states,” says Dr. Bess. People with bipolar disorder often switch between moods with distinct characteristics, such as mania and depression.

Bipolar disorder affects about 2.8% of people, though not all in the same way.

- Bipolar 1: The most “classic” type bipolar disorder with intense mood swings, where both their depression and the mania can be disabling.

- Bipolar 2: Bipolar depression and mood changes are similar to Bipolar 1, but mania episodes (also called hypomania episodes) are less severe. This is the most common type.

- Cyclothymic disorder: Occurs when someone experiences hypomanic and depressive symptoms. Mood swings may also be more spontaneous or fleeting than in bipolar 1 or 2.

Causes of bipolar disorder

The cause of bipolar disorder is unknown. There isn’t a single cause, but multiple—namely, a mix of genetic, environmental, and neurochemical factors. A leading theory is that the environmental factors may interact with genetic vulnerabilities to trigger the development of bipolar disorder.

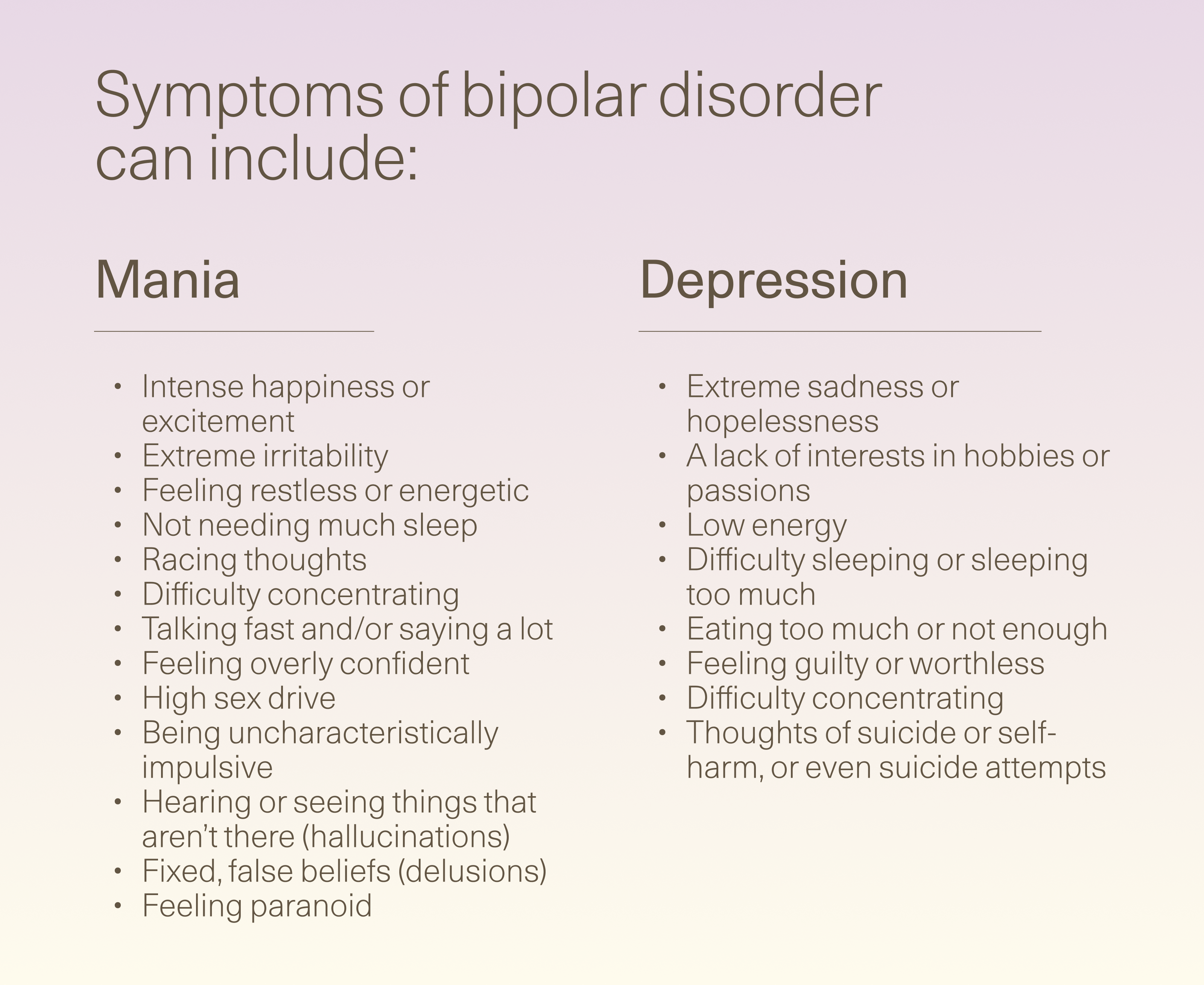

Symptoms of bipolar disorder

It’s best to think of bipolar disorder symptoms in two camps: episodes of mania and depression.

Mania can include:

- Intense happiness or excitement

- Extreme irritability

- Feeling restless or energetic

- Not needing much sleep

- Racing thoughts

- Difficulty concentrating

- Talking fast and/or saying a lot

- Feeling overly confident

- High sex drive

- Being uncharacteristically impulsive

- Hearing or seeing things that aren’t there (hallucinations)

- Fixed, false beliefs (delusions)

- Feeling paranoid

Depression can include:

- Extreme sadness or hopelessness

- A lack of interests in hobbies or passions

- Low energy

- Difficulty sleeping or sleeping too much

- Eating too much or not enough

- Feeling guilty or worthless

- Difficulty concentrating

- Thoughts of suicide or self-harm, or even suicide attempts

Diagnosing bipolar disorder

Like BPD, diagnosing bipolar disorder can take a long time. Many with the condition are first diagnosed with “depression”, only to find out they have bipolar disorder up to ten years later, when the mania occurs.

The diagnostic process includes:

- A comprehensive psychiatric evaluation

- An understanding of someone’s past behaviors and actions

- Interviews with family or loved ones.

Psychiatrists may also be on the lookout for family history, psychosis, non-responsiveness to anti-depressants, and hypomania symptoms in order to diagnose this condition.

Treatments for bipolar disorder

“For bipolar disorder, medication is much more important, especially mood-stabilizers like lithium, anticonvulsants (e.g. divalproex or carbamazepine), or antipsychotics,” says Dr. Bess.

Psychotherapy can also help people maintain daily routines that reduce the intensity of mood swings, though Dr. Bess notes that talk therapy isn’t always useful when someone’s in an extreme manic or depressed episode and may be too impaired to fully engage. In those situations, stabilization with medication is usually the first priority, and therapy often becomes more effective once acute symptoms have improved.

TMS also shows promise for bipolar disorder, particularly for treating depressive episodes. Admittedly, some are hesitant to use a treatment that only addresses the depression, though Dr. Bess mentions that TMS doesn’t make mania episodes worse.“In a sample of patients from our clinic,” he adds,

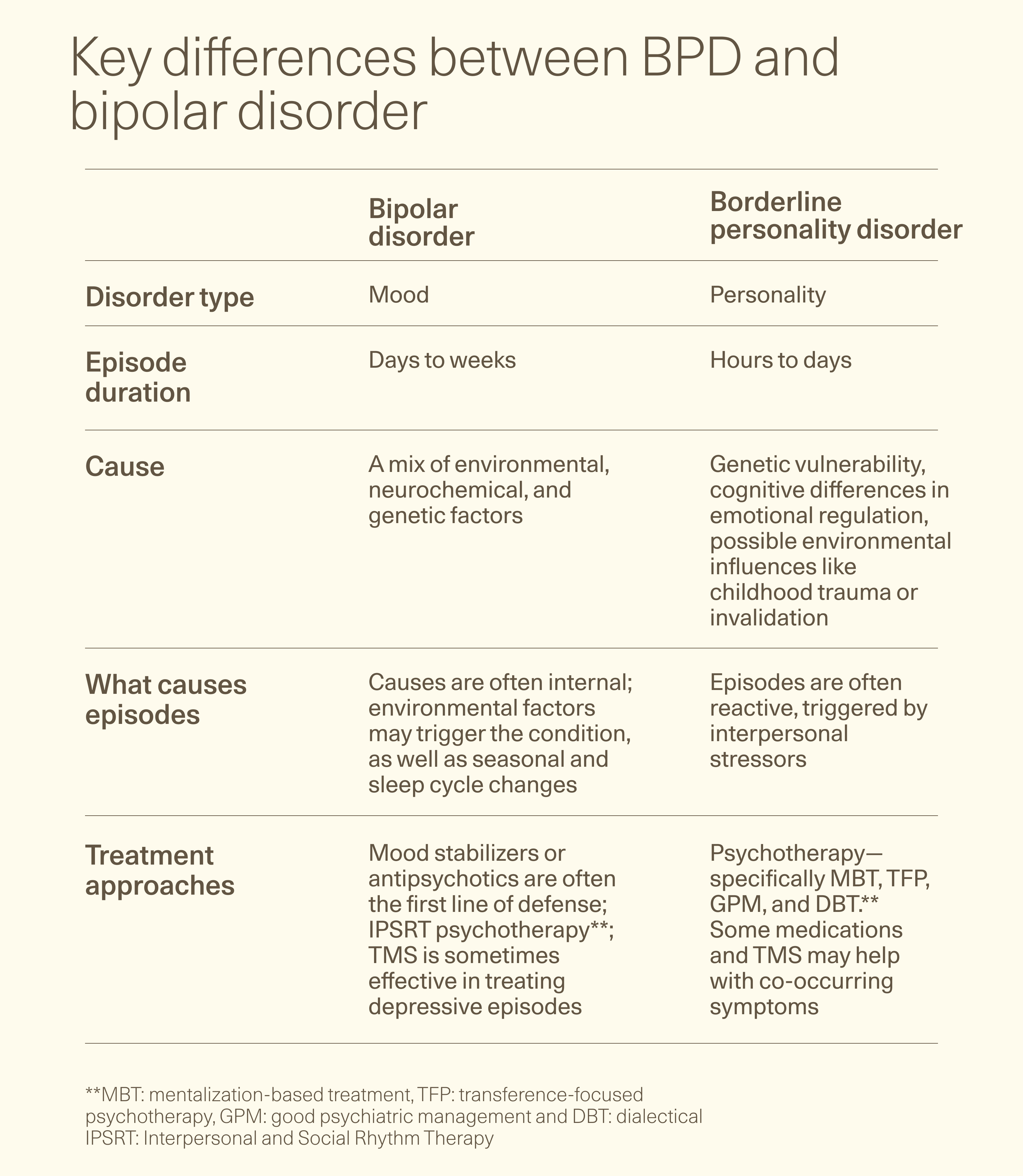

Key differences between BPD and bipolar disorder

By now, you probably have a good idea about the similarities and differences between BPD and bipolar disorder. But let’s take a deeper dive into how these two are distinct.

Mood vs personality disorder

The differences start with how psychiatrists classify these two conditions.

BPD is a personality disorder, meaning it reflects long-standing patterns of unstable relationships, self-image, and emotions that typically develop from a mix of genetic and environmental factors, such as trauma.

Bipolar disorder is a mood disorder, meaning it's characterized by distinct episodes of depression, mania, or hypomania that cause marked shifts in mood, energy, and activity.

Duration of episodes

Bipolar mood episodes can last weeks to months, whereas BPD episodes are on the scale of hours to days. With bipolar disorder, manic episodes last at least seven days and depressive episodes last at least two weeks. BPD episodes often don’t have a set time frame, and someone can shift from various emotions related to how they feel about themself and others.

What causes episodes

Both BPD and bipolar disorder are marked by episodes of unexpected behavior, whether it's actions that are aggressive and agitated or manic or depressed. The difference is what causes those episodes.

“Episodes in BPD are more often ‘reactive;’ that is, something sets it off,” says Dr. Bess. Interpersonal stressors are often to blame, such as a break-up or job rejection. “BPD ‘swings’ also tend to be more brief and can change direction quickly,” he adds.

By contrast bipolar moods last longer and are more likely due to neurochemical changes, though external factors can play a role. Dr. Bess explains, “While these mood states can be nudged by external factors, it really is just a nudge, not a wholesale switch like in BPD.”

Different treatment approaches

The final, and perhaps most important, difference is in how these conditions are treated. For BPD, psychotherapy is the first line of treatment. While psychotherapy can be helpful for bipolar disorder, it’s not as effective in the high highs and low lows, meaning medications play a much more important role.

For both, TMS is an emerging, effective treatment, mainly for bipolar depressive episodes and specific BPD symptoms (think: emotional dysregulation, depression, impulsivity, and mood swings).

Can you have bipolar and BPD together?

The answer is yes, with about 20% of those with bipolar 2 and 10% of those with bipolar 1 having BPD. BPD and bipolar together come with some unique challenges. Having both increases the risk of hospitalization, substance abuse, and suicide. It often means first-line treatments for one disorder, such as DBT therapy for BPD or mood stabilizing drugs for bipolar disorder, aren’t as effective and it takes longer to find a treatment that works.

That said, the right psychiatrist can treat both, often using treatments with evidence to help both conditions, such as TMS and some forms of talk therapy.

The bottom line

Bipolar disorder and BPD are both marked by extreme moods and behaviors that don’t serve the individual or help them develop strong relationships. Both can be treated, though approaches vary as the two stem from different causes. Because of the differences between BPD and bipolar disorder, it’s important to get an accurate diagnosis, which can take time.

Key takeaways

- Bipolar disorder is a mood disorder characterized by swings from mania episodes to depressive episodes. Borderline personality disorder is a personality disorder where someone acts impulsively or turbulently in personal relationships

- While both share a pattern of extreme behaviors and mood swings, the two are distinct conditions with different causes, treatment approaches, and symptoms.

- The team at Radial can help diagnose BPD or bipolar disorder and create an appropriate treatment plan, which may include a mix of talk therapy, medications, and TMS (though the “right” mix is different for everyone).

Frequently asked questions (FAQs)

Can BPD and bipolar disorder co-occur?

These conditions can co-occur. In fact, somewhere between 10-20% of people with bipolar disorder also have BPD. When both are present, treatment needs to work for both, and there is a higher risk for harmful behaviors, hospitalization, and substance abuse.

Is BPD often mistaken for bipolar?

BPD and bipolar disorder are often mistaken for one another since both cause extreme behaviors and superficially similar mood swings. However, these are two distinct conditions with different causes and symptoms. Different treatment approaches help both, highlighting the importance of getting an accurate diagnosis from a psychiatrist or psychologist.

Can trauma cause bipolar or BPD?

Trauma can play a role in both bipolar disorder and BPD. That said, trauma and invalidation from parental figures over time are two of the common risk factors for many psychiatric disorders, including BPD and bipolar disorder.

How long do mood swings last in bipolar vs BPD?

In bipolar disorder, mood episodes often have defined durations. Manic episodes last at least 7 days, hypomanic episodes last at least 4 days, and depressive episodes last at least 2 weeks. If untreated, these episodes can last longer. On the other hand, BPD mood swings are usually shorter and more reactive, usually lasting a few hours or days. The swings also stem from how the individual feels about others and themself, often shifting from euphoria to anger or despair in a short period.

Editorial Standards

At Radial, we believe better health starts with trusted information. Our mission is to empower readers with accurate, accessible, and compassionate content rooted in evidence-based research and reviewed by qualified medical professionals. We’re committed to ensuring the quality and trustworthiness of our content and editorial process–and providing information that is up-to-date, accurate, and relies on evidence-based research and peer-reviewed journals. Learn more about our editorial process.

Let's connect

Get started with finding the right treatment for you or someone you care about

Get started